Sit where the light corrupts your face,

Mies van der Rohe retires from grace.

And the fair fables fall.

– Gwendolyn Brooks, In the Mecca

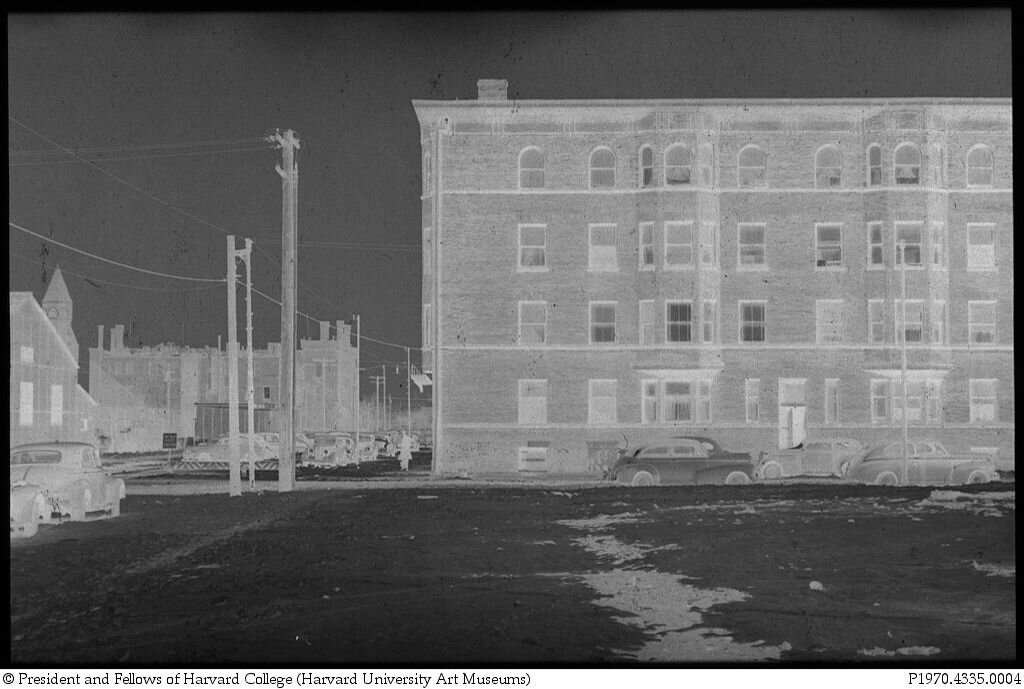

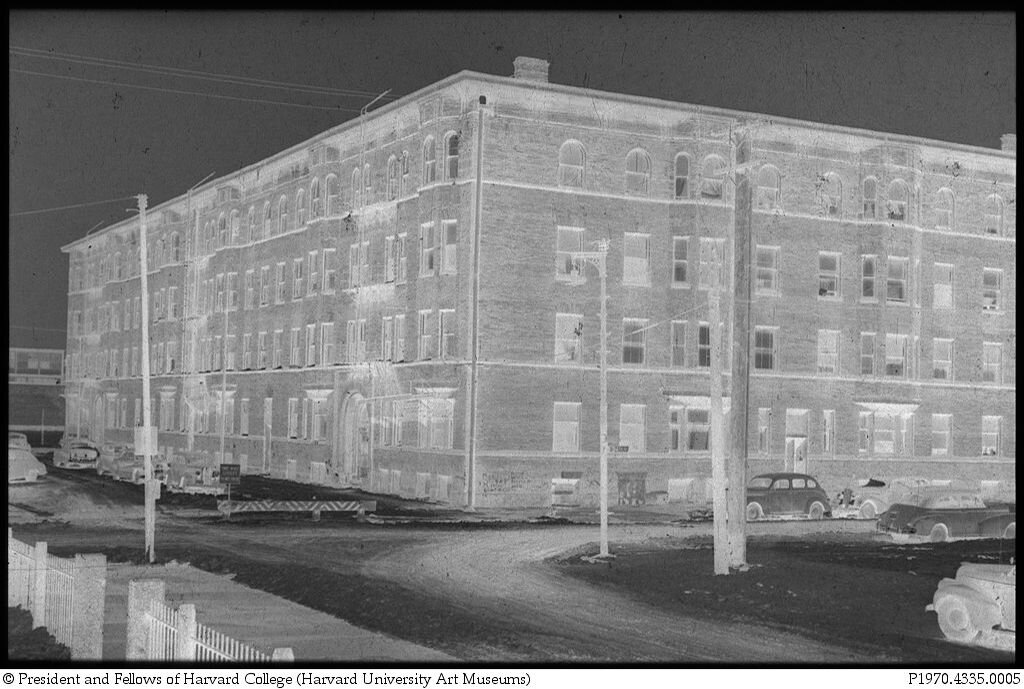

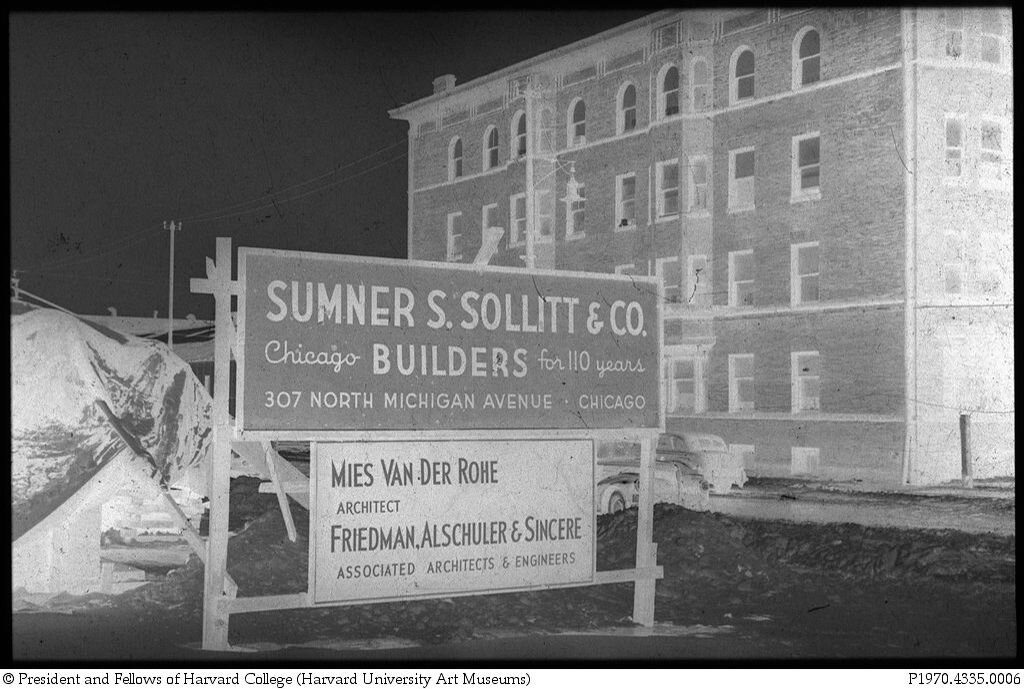

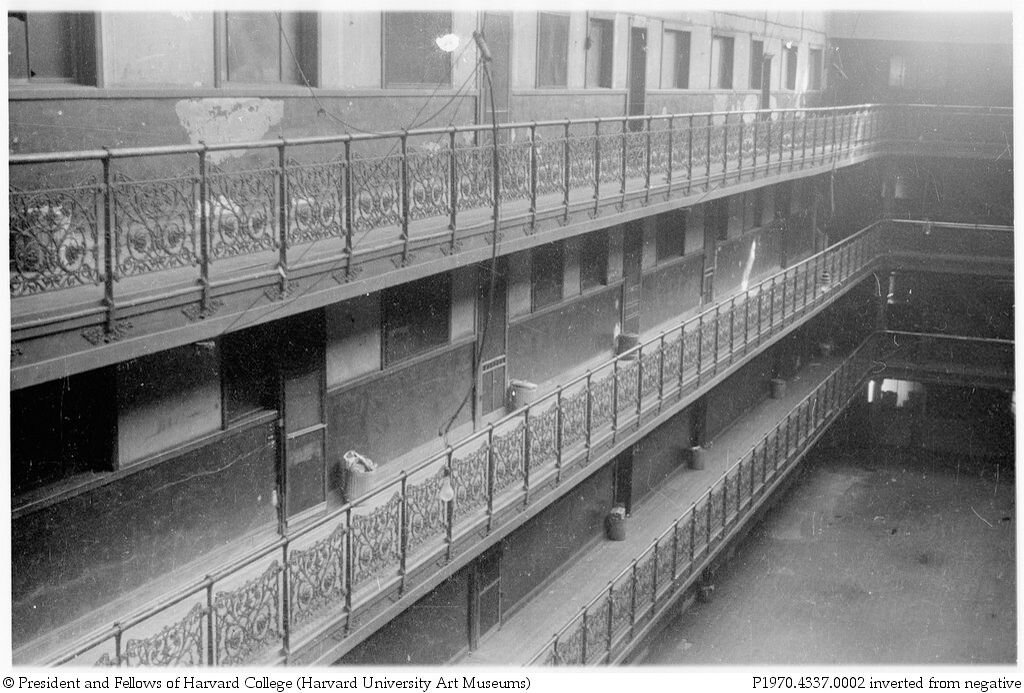

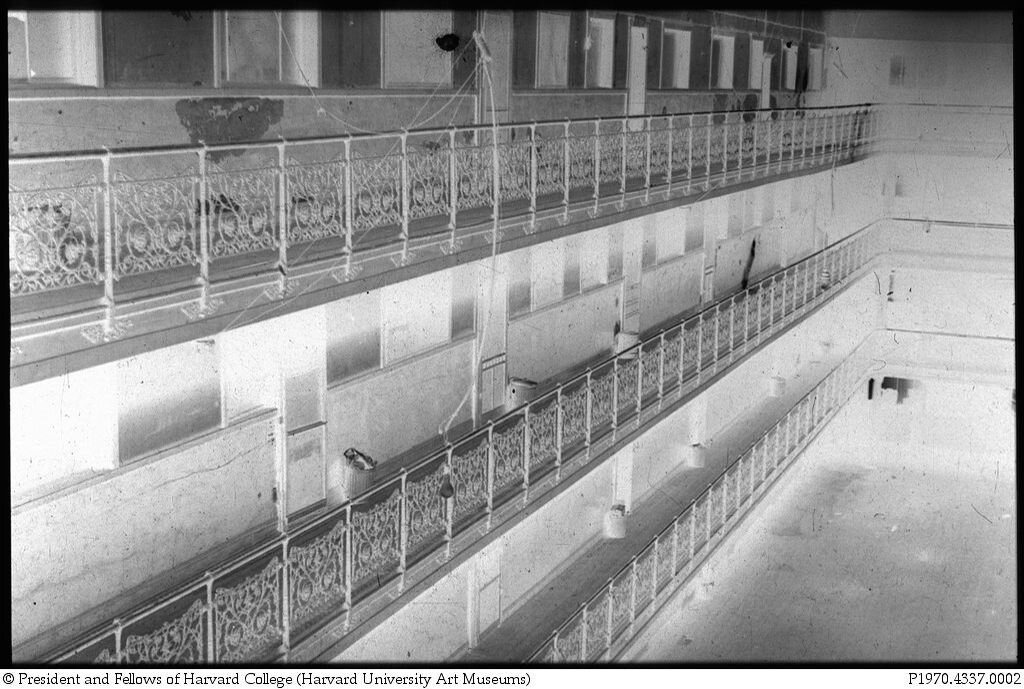

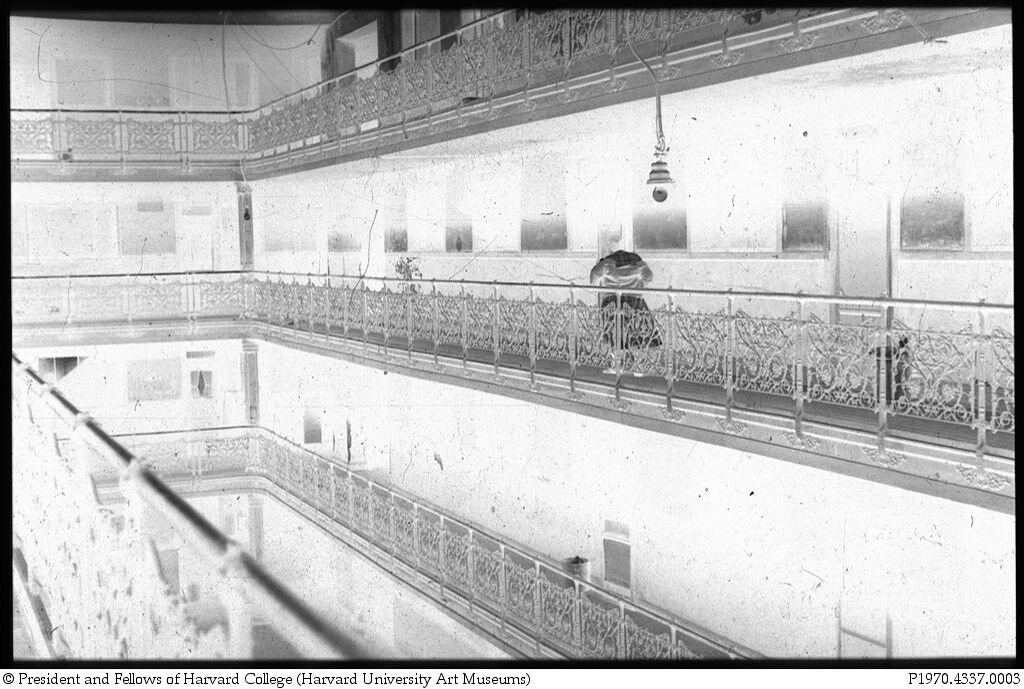

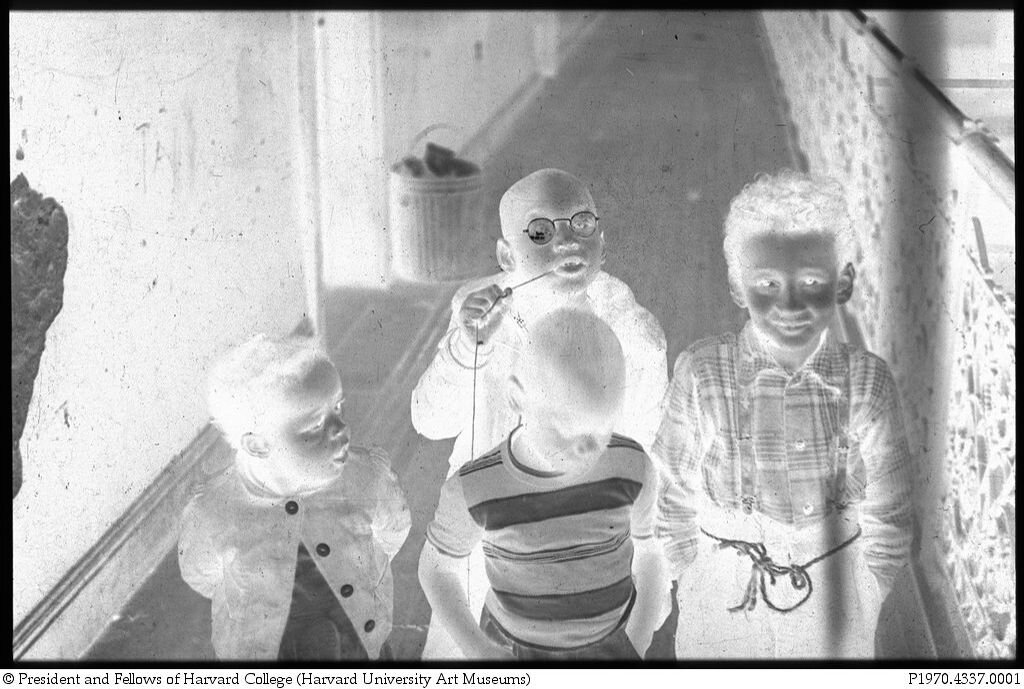

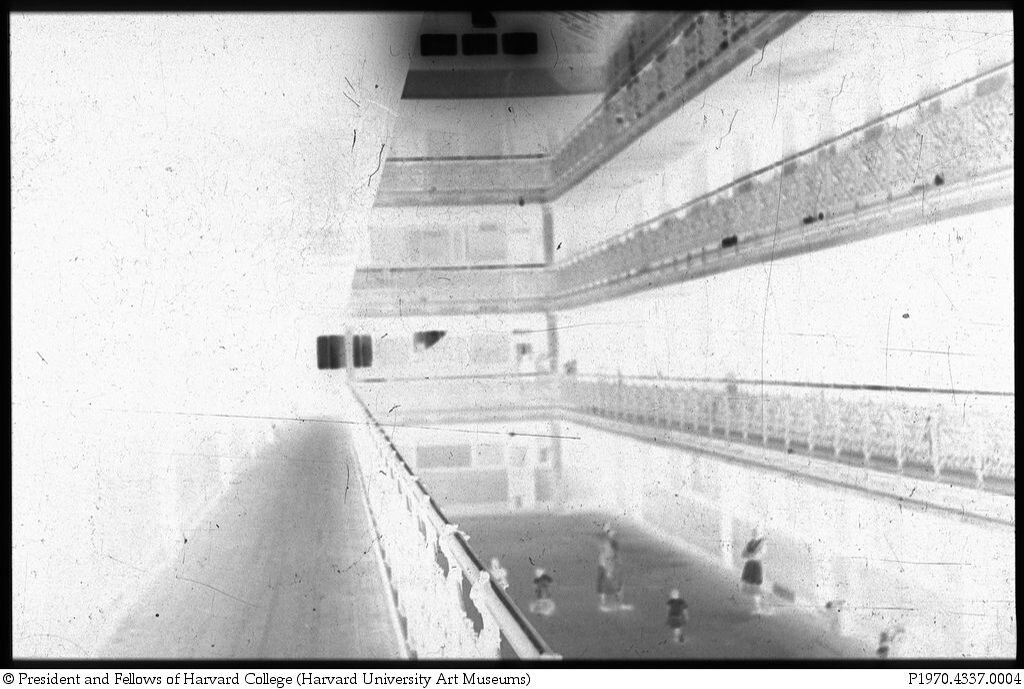

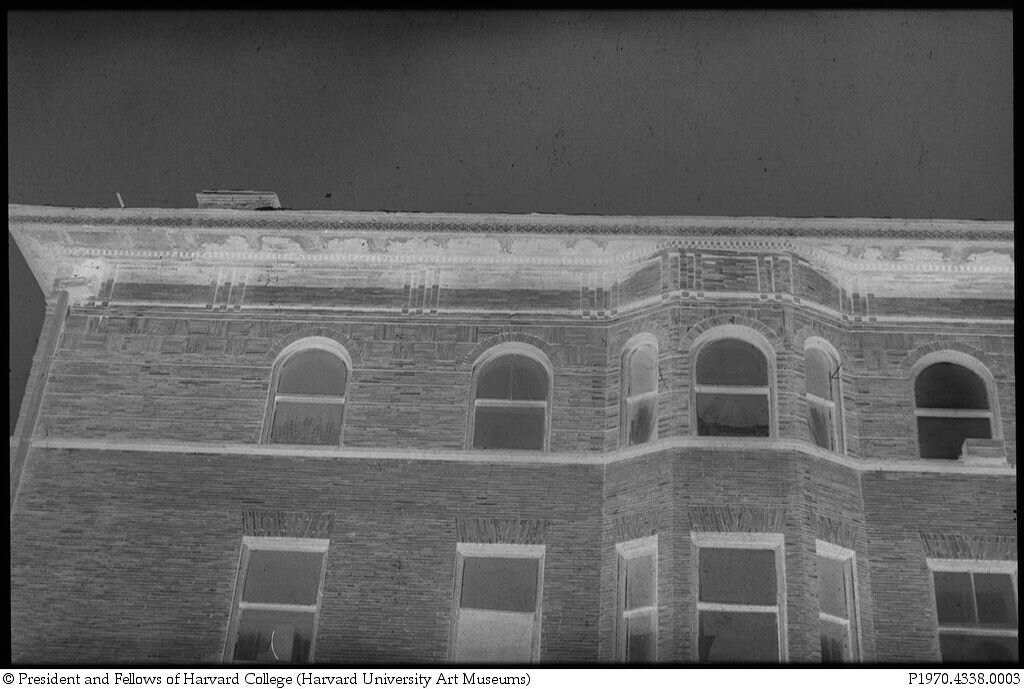

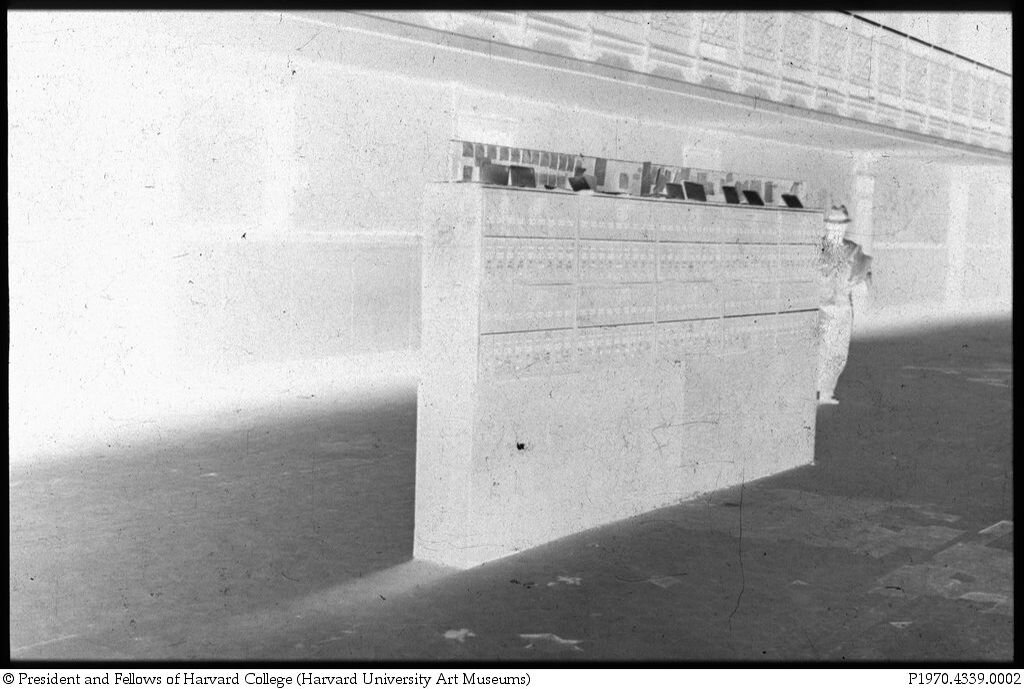

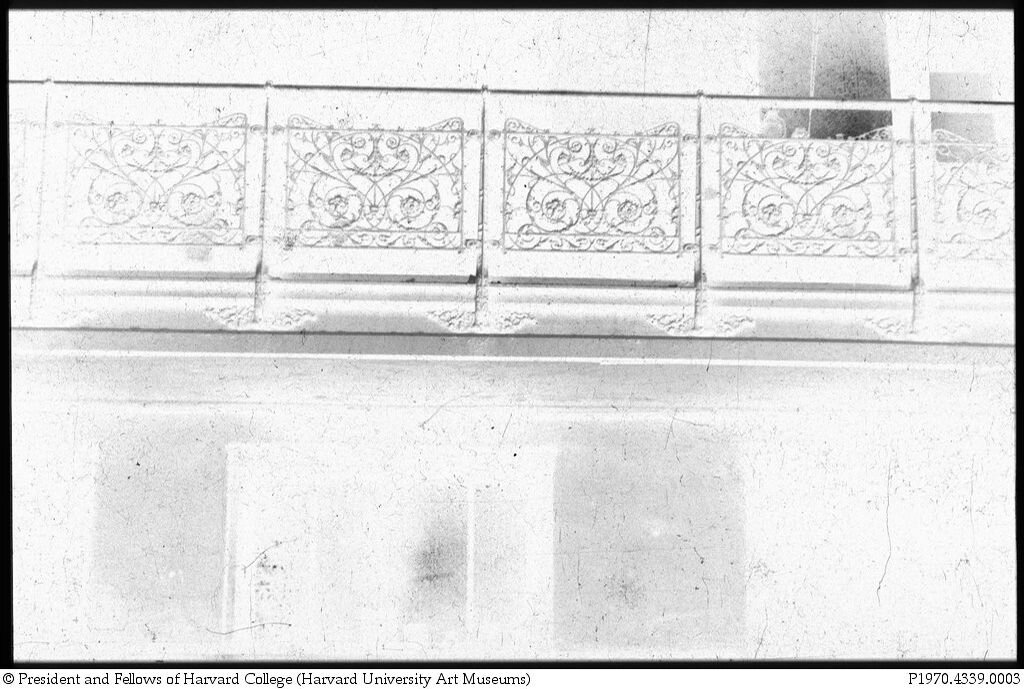

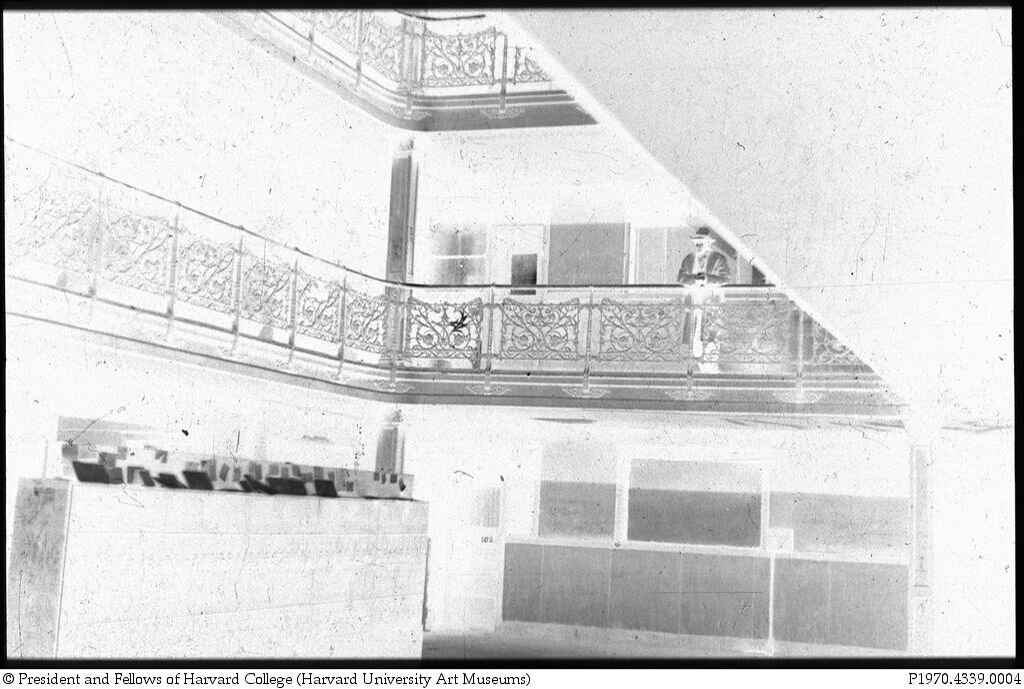

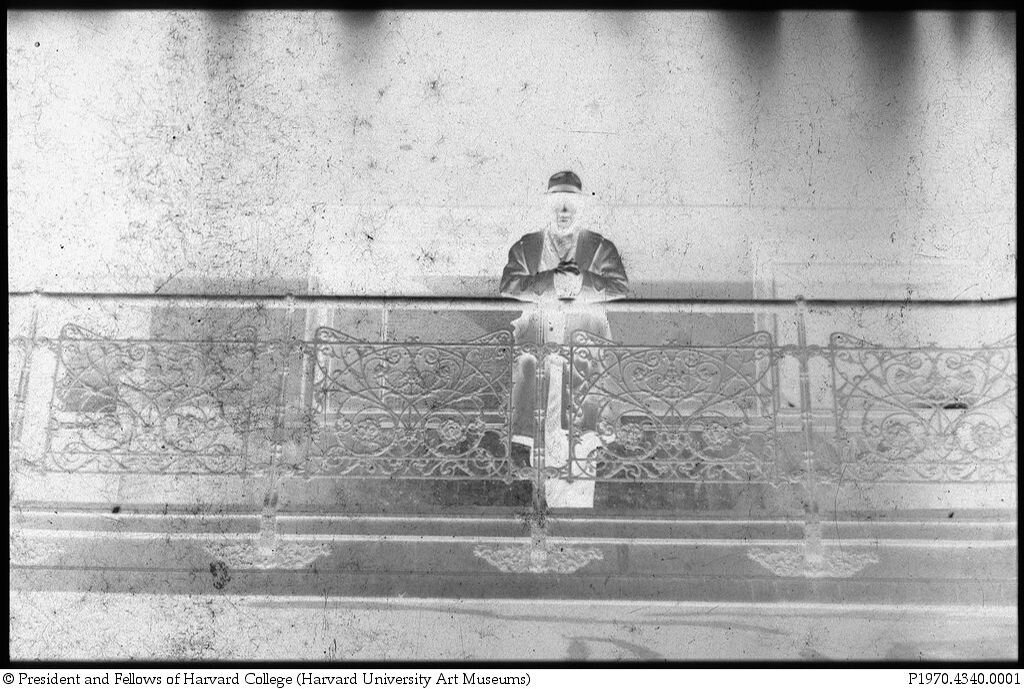

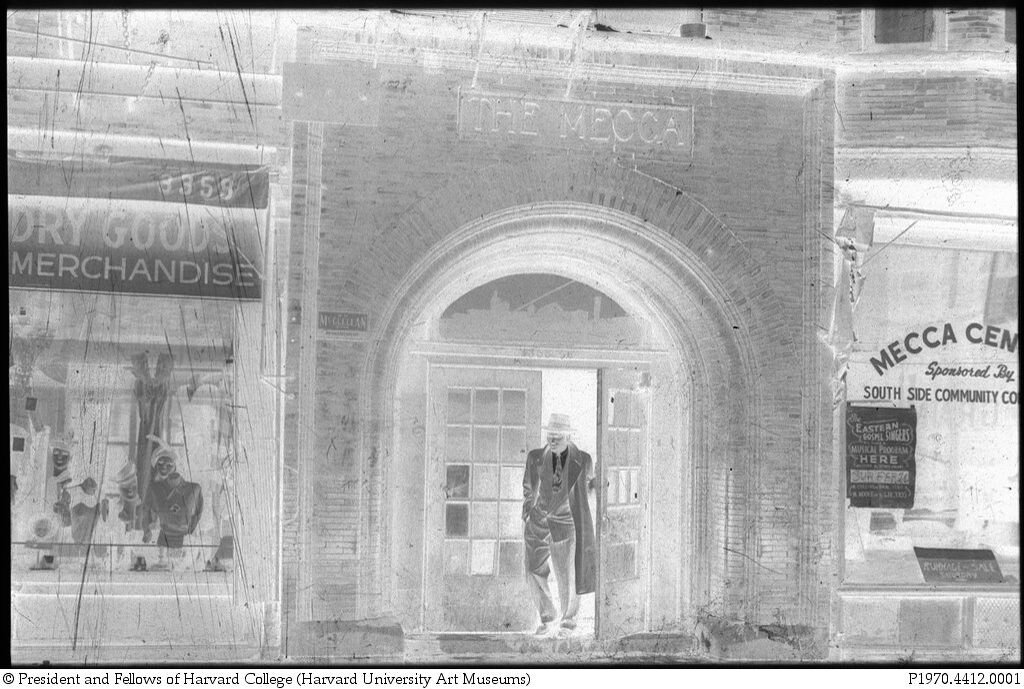

In December 1950, Harper’s Magazine published an essay called “The Strangest Place in Chicago” by John Bartlow Martin with illustrations by Ben Shahn. Martin describes a once glorious 19th century apartment building called “The Mecca” located in Chicago on 34th Street between State and Dearborn. Designed in 1891 by Willoughby J. Edbrooke and Franklin Pierce Burnham, The Mecca was an architecturally significant structure representative of Chicago’s claims to modernity and innovative urban planning through the combination of high-density living with more suburban residential features. By the 1920s, the building had become a “mecca” for African-Americans aspiring to the middle class. The great poet Gwendolyn Brooks worked there, and wrote about it in her book of poetry, In the Mecca (1968). Civil rights pioneer Ida B. Wells and heavyweight champ Joe Louis lived there as well, and the structure even inspired a popular song, “Mecca Flat Blues.”

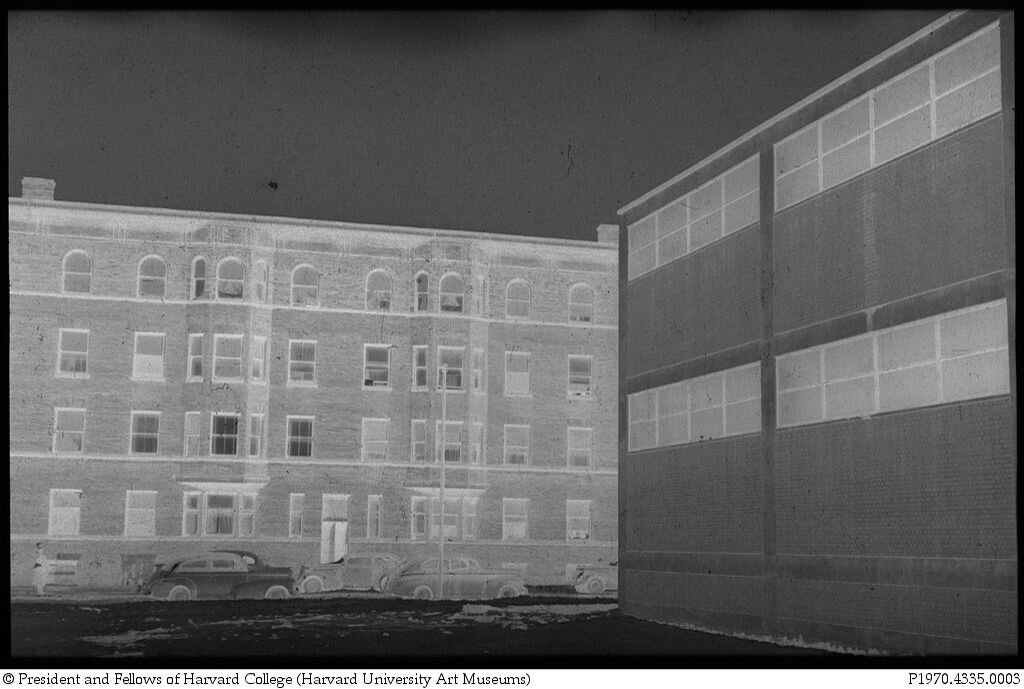

The Mecca was purchased quietly in 1938 for the planned expansion of what would become the Illinois Institute of Technology in 1940. Throughout this decade, the IIT sought to expel what had become nearly 2000 tenants by refusing to put money into maintenance and repairs, and then resorting to eviction proceedings. In 1950, the remaining tenants responded with mass protests. Nevertheless, The Mecca was demolished in 1952 to make way for Mies van der Rohe’s masterwork, S. R. Crown Hall, which now sits precisely on its former footprint. This site and its Bronzeville environs thus evoke many fascinating themes of displaced architectures, competing visions of modernism and utopia, and conflicts in popular and cultural memory.

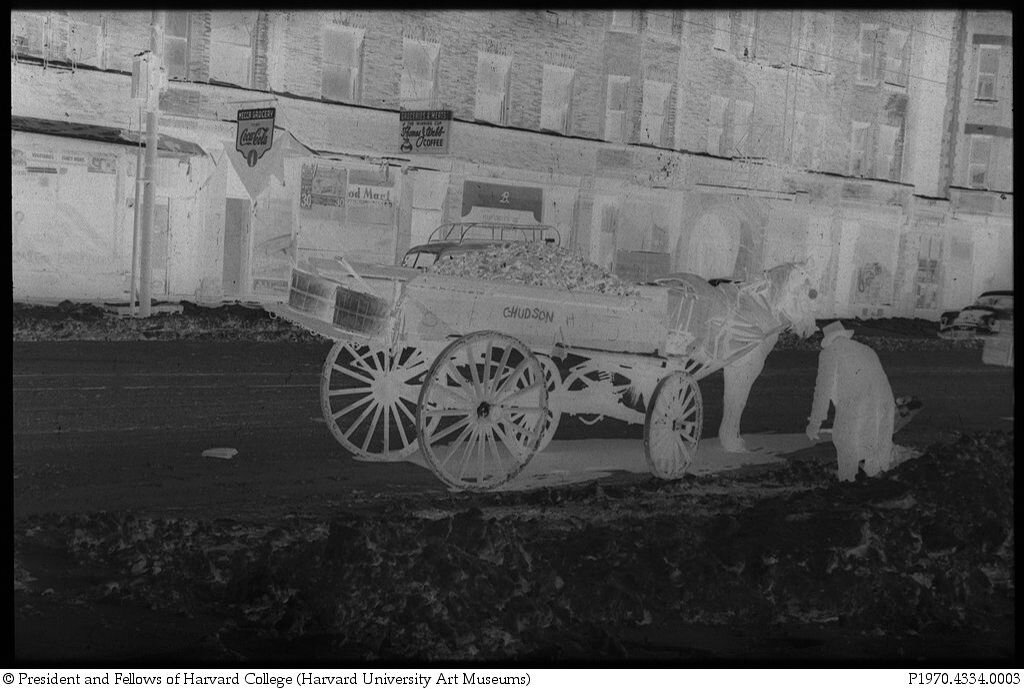

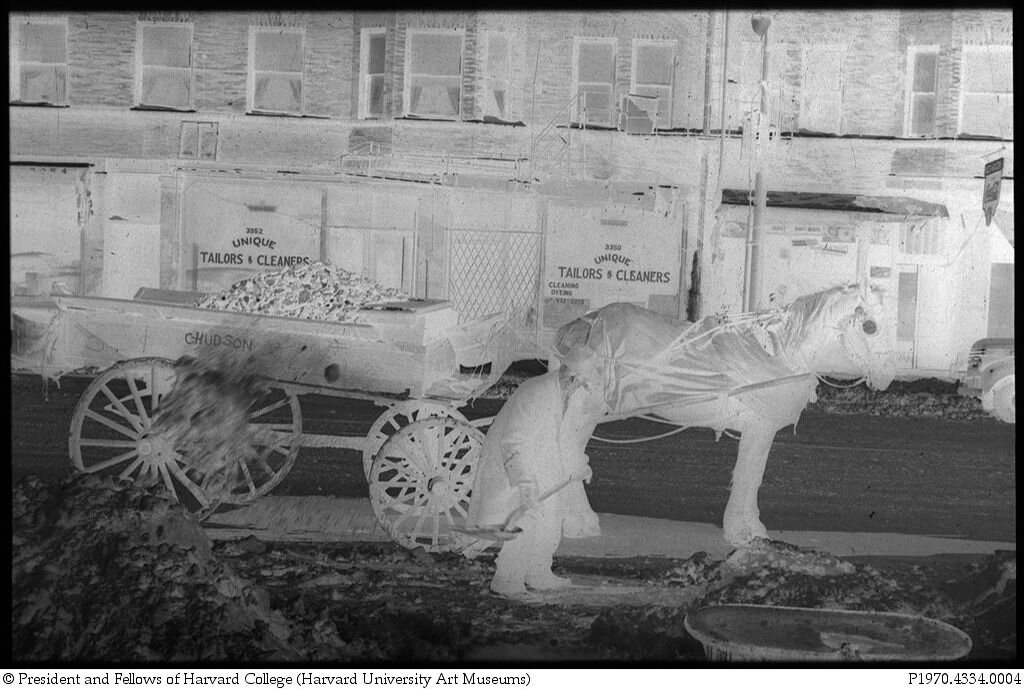

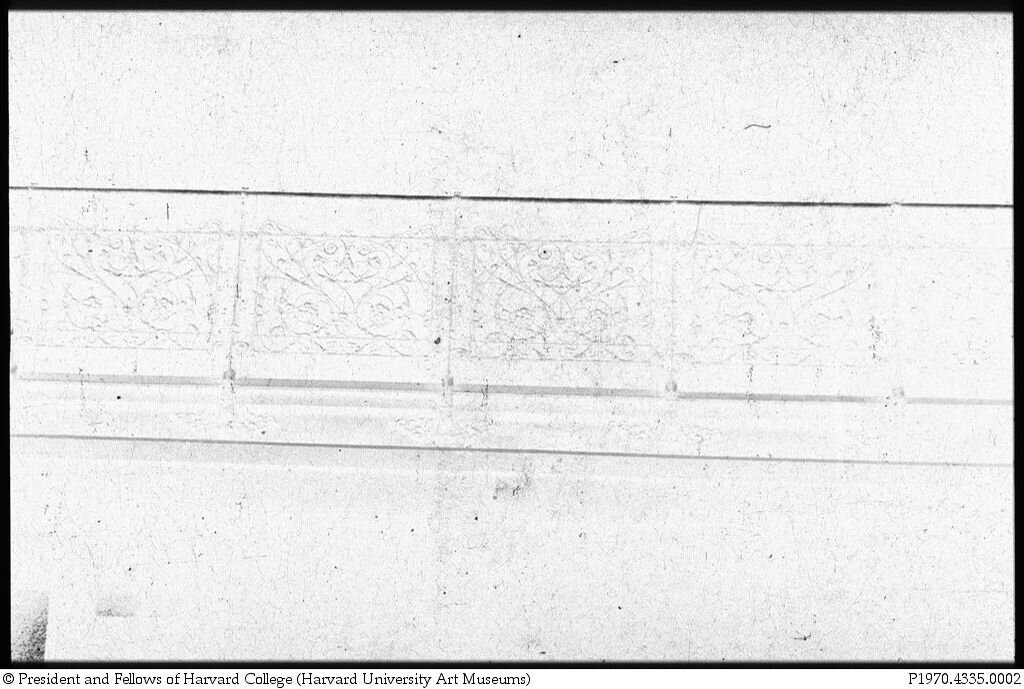

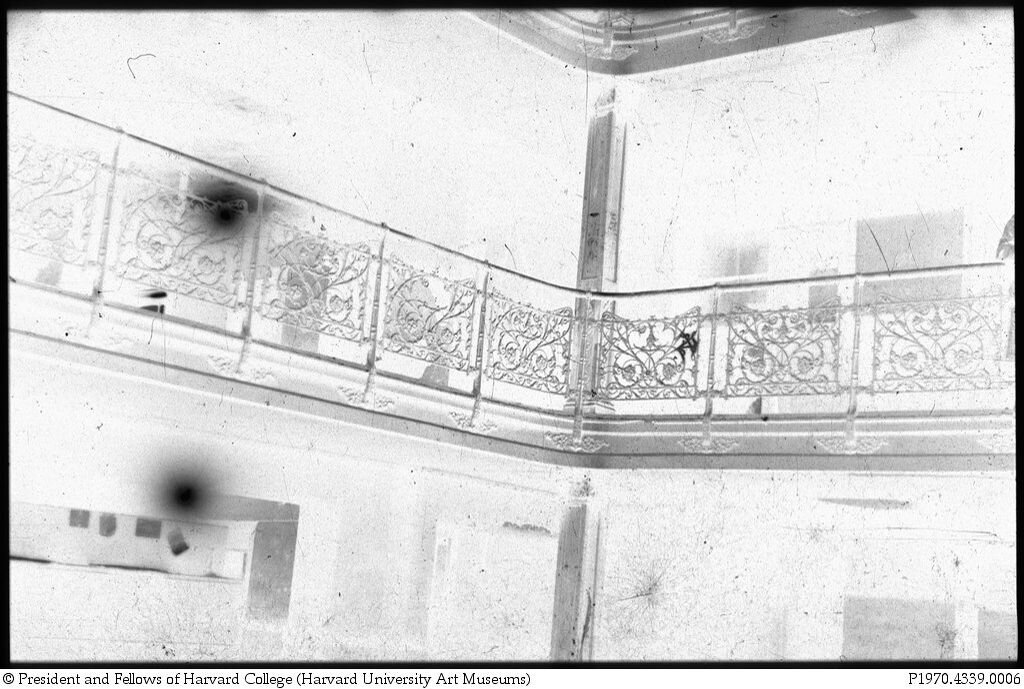

I call Returning a “reanimation” for several reasons. The elements of this work are taken from photographs Shahn made as records for his drawings. These images were probably not meant as artworks, but rather only as aides-mémoire for Shahn’s drawings. Now preserved at the Harvard Art Museums, they may be viewed online as a collection of 32 negatives. I find these negative images to be haunting, not only because they present a disappearing world now lost, but also for their pictorial density and abstraction. Shot in winter, and in largely depopulated exterior and interior spaces, the reversed tonalities of these images bring out volumes and shapes that disappear into their documentary and representational positive counterparts. (Oddly, in most cases black skin preserves its darkness in the negatives as if an inescapable condition of existential surface—there are no “white masks” here.) The negatives also lend emotional gravity to the nearly empty spaces that once housed thousands of inhabitants. The surface of most of the negatives is scratched or abraded, and marred by dust. One feels the corrosive force of time upon them, eroding their legibility yet giving them the materiality of history as a medium with a certain density and opacity.

Returning consists of several possible versions though the aim of each is to reanimate these haunted images back into the present, or whatever multiple, contradictory presents we inhabit in viewing them. Each version of the projections orders the images as the imagined trajectory of an anonymous though invested observer around the exterior and into the interior of the building. (One could imagine this sequence as a record of Shahn’s own wandering though the print numbers on his contact sheets suggest otherwise.) Another powerful inspiration is the complex narrational voice of Gwendolyn’s Brooks’s In the Mecca and the implied spatial and temporal structure of Brooks’ own haunted poem, itself a reanimation of The Mecca and its inhabitants as a mother returns home, and then searches for her lost child.

The core form of Returning is structured as a sequence of 26 “passages” organized as languid cross-fades from negative to positive images—at the midpoints of these transitions each passage appears as a strangely embossed bas-relief. Here Shahn’s photographs are literally reanimated. The implied movement is less a reversal than a passage through variable densities that vacillate between abstraction and figuration, which in turn suggest the ambiguity and intractability of historical documents with respect to the reanimation of the disappeared. There is no dialectic here but rather only a series of variable intensities and intervals.

I am hoping to install Returning in Crown Hall as a large scale projection onto its interior glass front.

View Returning: a reanimation on Vimeo.

Download a PDF of John Bartlow Martin’s “The Strangest Place in Chicago.”

Returning: a reanimation was produced with support from the Richard L. and Mary Gray Center for Arts and Inquiry, and the Department of Visual Arts at the University of Chicago.

Ben Shahn’s Mecca photos are reproduced with permission of the Harvard Art Museums; copyright by the President and Fellows of Harvard College.